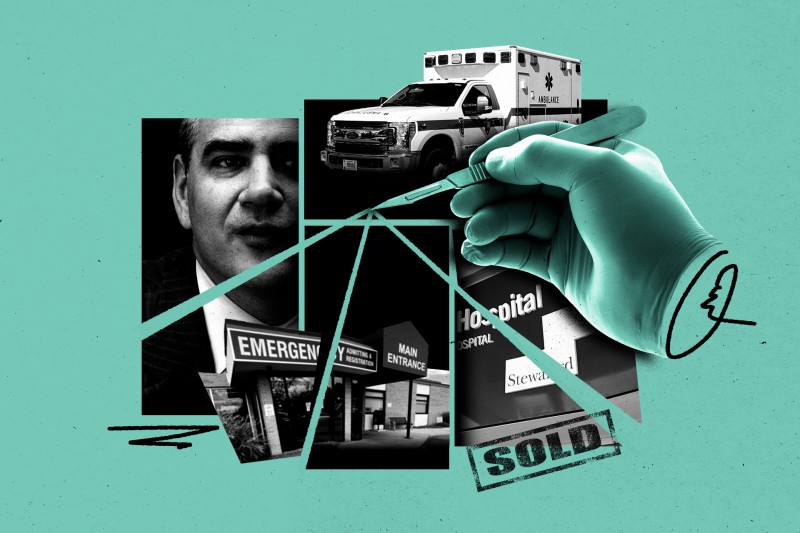

How Private Equity and an Ambitious Landlord Put Steward Health Care on Life Support

The Road to ‘World Domination’

By the end of 2017, MPT was already listing Steward as its largest source of revenue, accounting for 27 percent of the REIT’s earnings, even though Steward itself wasn’t profitable. But the companies had been growing rapidly — hand in hand.

Steward had been buying up hospitals across the U.S. with MPT’s encouragement. In September 2017 it acquired IASIS Healthcare in a deal valued at more than $2 billion, taking the number of hospitals it operated to 36, including the top-performing Davis and Jordan hospitals in Utah.

MPT indirectly financed the deal by giving Steward $1.4 billion for 11 of the properties almost immediately after Steward acquired them. Steward would then lease them back from MPT. MPT issued mortgage loans that added to Steward’s debt load, and financed the deal by issuing higher-risk unsecured corporate notes.

Documents seen by OCCRP show that MPT used mortgage arrangements as a way to pump money into Steward. For example, after MPT acquired the real estate of St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Houston for $131.3 million in 2017, it “sold” the property back to Steward just six months later for $148 million by issuing Steward a mortgage note. In late 2018, MPT acquired the real estate back from Steward by canceling its mortgage debt and added an unspecified “cash consideration.”

MPT’s communications with the SEC show Steward’s purchase of St Joseph’s briefly pushed it into representing more than 20 percent of MPT’s assets, meaning that the REIT should have filed Steward’s audited financial statements for 2017. (As a private company Steward did not usually have to file financials, unless requested by the SEC). When asked by the SEC why it had not submitted Steward’s financial statements even though it had crossed the 20 percent asset threshold, MPT said it was because St Joseph’s had quickly been sold back to MPT.

By 2019, Steward’s annual lease payments to MPT were $350 million, according to MPT’s filings, representing 42 percent of MPT’s total revenues, despite accounting for less than 9 percent of the hospitals in its portfolio. (MPT did not respond to questions on this apparent imbalance.)

Meanwhile, Steward’s international arm had secured a massive deal to take over Malta’s state hospitals for $2.1 billion. The deal would eventually be rescinded and led to an investigation into whether the Prime Minister had been bribed, as OCCRP has reported.

But financial filings and internal communications seen by OCCRP show that despite its ambitious plans and global expansion, Steward was in fact falling apart.

How MPT Bankrolled An Ailing Steward

MPT’s Aldag insisted in a February 2019 earnings call that Steward was “doing exceptionally well” — even though Steward’s annual report for 2018 had just shown a $280 million loss. Aldag again repeated on an earnings call the following year that Steward “continues to see good progress, both operationally and financially.” As a private company, Steward did not have to publish its annual reports, so MPT investors would have had no way of knowing its true financial prospects. (Aldag did not respond to a request for comment.)

By 2020, Cerberus executives had privately conceded that Steward was in financial peril, and the private equity firm negotiated exiting the business.

It turned out that Steward looked from the outside like a successful business in part because MPT was finding discreet ways to bankroll the hospital chain. Internal emails obtained by OCCRP detail just how dependent Steward had become on MPT for its survival.

In 2018, MPT began making direct loans to Steward, but may not have disclosed the extent of its lending in a timely manner — or in some cases, at all. Under SEC rules, publicly traded companies like MPT are expected to announce significant or “material” events to shareholders within four days. However, some of the loans MPT made to Steward were not disclosed for more than three years, and in some cases OCCRP could find no evidence that MPT had ever made the required filings.

Emails suggest that these loans were being used to cover the exorbitant rents that made the hospital chain look so lucrative to Steward’s investors.

During the bankruptcy proceedings, Steward’s lawyers quoted its creditors as saying that MPT’s leases were “disguised financing,” and that it had resorted to sending the hospital chain money to cover them.

In response to a question about this allegedly disguised financing, the spokesperson for de la Torre said: “As we have cited numerous times in our communications with HELP Committee, Dr. de la Torre is prohibited from discussing the bankruptcy process based on confidentiality obligations.”

Over the course of 2018 and 2019, internal documents show that MPT lent Steward more than $53.5 million in working capital in three tranches. In 2023, under pressure from the SEC, MPT gave details of seven outstanding loan tranches totalling $214.9 million — but that number falls far short of the loans evidenced in the documents and communications seen by OCCRP.

Simone, the REIT analyst from investment researcher Hedgeye, said MPT appeared to be funding Steward’s operations, acting more as an owner or major investor in the company than a landlord. (MPT blamed Simone and Hedgeye for much of the short interest in the company and records obtained by OCCRP show MPT and Steward asked business intelligence firms to disseminate negative information about them.)

“MPT behaves like Steward is 100% theirs,” Simone said.

In response to questions from OCCRP, MPT said it had made all the required disclosures regarding Steward. “MPT stands firmly behind our rigorous underwriting process as well as the completeness and accuracy of our disclosures. We have unfailingly disclosed each of our transactions – including those with Steward – as and when required under applicable securities law. ”

De la Torre’s representative said the former CEO still believed Steward’s partnership with MPT was a “prudent decision” because the trust “represented a long-term capital partner whose returns on investment were conditioned upon Steward’s continued success.”

“MPT, as a REIT that owns public hospitals, is by its own definition a long-term investor. Cerberus, as a private equity firm, by definition has a different incentivization structure governing its Steward investment, rendering it more focused on short-term return for its investors,” she said. De la Torre was not involved in MPT or Cerberus’ financial reporting, she added.

As Steward Sank, Executives Prospered

As Steward’s debt grew, de la Torre and other executives continued to prosper. Besides the debt based dividends that de la Torre and his team earned, variously reported as $55 to $71 million in 2016, leaked documents show that they benefited from huge loans including through share and off-balance schemes, some of which were later written off.

Internal emails show that in 2018 multiple Steward executives had outstanding loans with the U.S. arm of Steward totalling more than $3 million. Some executives’ loans featured on Steward’s balance sheet but others did not, including an unspecified amount loaned to de la Torre, according to the emails. A loan to Steward U.S. President Mark Rich was due to be forgiven, the emails say. The loans were secured by Steward shares owned by the executives.

Leaked emails show that in 2021 Steward executives were also being loaned money by the healthcare company’s international arm, Steward Health Care International (SHCI) which offered de la Torre a credit line of up to $27 million, with the repayment transferred to companies he owned.

In a response to a question on this, de la Torre’s spokesperson said: “In 2018, Steward Healthcare International was a subsidiary of Steward Healthcare System. Therefore, any loan between these two entities at this time reflects an arrangement between a parent company and a subsidiary. We are not aware of promissory notes from Steward Health Care System for $27 million or $3 million.”

Internal correspondence shows the cavalier way in which the executives discussed the large sums they were spiriting away. In an email titled “cash for the boss, Rich asked SHCI in late 2022 to deposit 500,000 euros into an account controlled by de la Torre. When asked if SHCI would be repaid, Rich responded, “Thanks on the 500. I doubt you will be getting it back anytime soon.”

Armin Ernst, the president of the international arm of Steward, also received a $2 million loan from SHCI. The company’s lawyer explained the repayment of the loan to Ernst: “short of saying that the loan will not be claimed is the only wording[,] which without saying is our position.” Ernst did not respond to a request for comment.

In 2021, 8.8 million euros went toward a Madrid residence that de la Torre used as his European base, documents obtained by OCCRP reveal. De la Torre also lived lavishly in a baronial Dallas residence, and had exclusive use of a corporate jet and a penchant for buying yachts.

A Steward bankruptcy document shows de la Torre took $4.2 million in salary from Steward Health Care Systems, which ran the U.S. hospital operations, in the year preceding its bankruptcy declaration, from May 2023 to May 2024.

A spokesperson for de la Torre said his salary was consistent with other executives of his stature. “A nationally recognized compensation consultant analyzed and made recommendations for Dr. de la Torre’s salary, and his salary was found to be, and remains on the lower end of the recommended salary range for an executive like Dr. de la Torre.” The spokesperson declined to name the consultant that made the recommendations.

De la Torre failed to comply with a subpoena to testify in September at a hearing of the Senate’s Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, led by Sanders, on Steward’s bankruptcy. Through his attorney, de la Torre argued that his testimony would conflict with the bankruptcy process.

In a response to emailed questions, a spokesperson for Mark Rich said:

“Mark Rich resigned as CFO of Steward Health Care in 2017, and did not hold that position again until March 2023. As such, he was not in a position to oversee the vast majority of the instances you have posed, most notably the 2021 dividend. Mark Rich has never received a loan from SHCI.”

The Final Battle

After years of trying to take control of Steward, MPT made a final push to oust Cerberus in 2020. A presentation to MPT’s board in May that year said that Cerberus’s continued ownership would “impede MPT’s opportunity to grow with Steward.”

The slide deck from the presentation reveals more about the bitter battle that had been taking place between the private equity firm and the REIT.

“More recently, during 2019, we have been in discussions with Steward and Cerberus to try to achieve our collective goal of MPT owning a significant stake in Steward while taking out Cerberus’ ownership,” the slides say. “Once again, Cerberus attempted to re-trade management by threatening to manipulate Steward into bankruptcy with the belief that they can force MPT to renegotiate lease terms.”

But as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the world in early 2020, putting extra pressure on hospitals, Cerberus finally agreed to exit. By that time Steward was effectively broke and needed $510 million to “keep the lights on,” including covering capital expenditure, rent, and interest on its debt, as well as $750 million in capital investment over seven years, according to a confidential April 2020 memo authored by Cerberus’ head of operations, Chan Galbato. Meanwhile, earnings before taxes and rent was around $375 million but likely less, the memo said.

The memo argued that Steward’s management had “deluded itself” on the hospital chain’s expected operating earnings. Galbato added that de la Torre had little ability to manage a business and that a “real conversation” was needed with MPT on “the art of the possible.”

In a response to a question on the memo, Cerberus called it “a thought exercise by an operating executive who had been asked for his ‘10,000 foot’ view during the earliest months of the COVID-19 pandemic – a time of great uncertainty for healthcare businesses around the world. The very first sentence of the memo states that ‘comments should be regarded as hypothesis needing some clarification and validation.’” Cerberus added that “the cover email transmitting the April 2020 document to which you refer clearly stated that it was specifically offered as a ‘discussion document,’ the content of which needed to be ‘discussed and analyzed.’”

Eventually MPT, Cerberus and Steward figured out a deal in which everyone would get something. To work out the details of the 2020 carve up, MPT’s management said in internal communications that they needed to “get creative.” The result of that creativity was dubbed “Project Easter.”

Cerberus agreed to sell its controlling ownership share of Steward (listed then as 86.3 percent percent) to de la Torre and his management team for $350 million via a promissory note that the hospital chain had no means of paying. It would later get the money from MPT to retire that note, albeit for the slightly lesser amount of $335 million.

MPT’s equity participation rights in Steward (the rights to dividends and earnings from the sale of assets) quietly increased to 37 percent with the deal. The MPT board presentation illustrates the REIT’s still ambitious plan for the hospital chain: The slide deck says MPT values the franchise at $2.5 billion and adds that de la Torre and Steward management had been exploring various “international opportunities.”

But the whole Project Easter carve-up came with a major caveat — hundreds of millions had to be be pumped into Steward.

Documents reviewed by OCCRP reveal that MPT, Cerberus, and Steward were concerned that they could be accused of cashing out of Steward at a time when the hospital chain was insolvent.

The May 2020 presentation to MPT’s board said that $400 million would be injected into Steward for two reasons: to keep the hospital chain afloat during Covid and to “provide protection to Cerberus from a possible fraudulent conveyance claim.” Such a claim would allow creditors or a bankruptcy court to claw back money that it received for its equity interest when Steward was insolvent.

To raise that $400 million, MPT and de la Torre would form a new company to buy Steward’s international rights and assets for $200 million, according to the MPT board presentation. The other half would be raised by acquiring Steward’s Davis and Jordan hospitals in Utah for $200 million more in cash than they were worth. Those deals were detailed in the final agreement signed by all parties.

But there was an extra twist — not all of that money turned up on Steward’s balance sheets.

An email from Steward’s Mark Rich in February 2023 reveals that the $200 million cash due to be raised from the sale of the Utah hospitals was not going to be found by auditors because it had been paid out to partners.

“So we have to back track all this bad history and bad explaining and “secret decoder ring topside only entries” and come up with a simple, supportable way to explain this. Everyone thinks the audit of Davis/Jordan will explain this. Guess what? It won’t. It’s all buried probably in partner’s equity,” he says.

In internal emails in December 2020, MPT vice president and CFO Steve Hamner mentioned the REIT would expect to consent to a dividend payout of $111 million off the back of the Project Easter deal, the majority of which would go to de la Torre, who owned 80.7 percent of Steward by that point. MPT itself would get $11 million.

Around that same time, de la Torre was reported by the Boston Globe to have bought the Amaral, a 190 foot superyacht that cost $40 million.

Project Easter also included permission for Steward to change its operating agreement so that MPT lost the right to approve the issuance of dividends by Steward. That meant de la Torre would be free to issue himself dividends of up to $500 million at any time.

In a response to a question sent to de la Torre about the Cerberus exit deal, the spokesperson said: “The only benefit Dr. de la Torre received from the May 2020 recapitalization was to ensure that the hospitals were not put into a bankruptcy process in the middle of the pandemic and that they had sufficient funds to continue operations during COVID.”

Cerberus told OCCRP of the deal: “Cerberus exited Steward in early May 2020 … when we exited, the company was financially healthy and we did everything we could to prudently prepare it for the uncertain impact of COVID-19 by specifically structuring the May 2020 transaction to require the infusion of $400 million of fresh capital into the company, with zero additional debt or leverage.”

With the Project Easter carve-up complete, Steward staggered on, propped up by loans and advances from MPT.

In 2022, with Steward billions in debt to MPT, the hospital chain’s chief financial officer said in an internal chat, apparently working through how much Steward could borrow, that the firm was “deep in the zone of insolvency,” before hours later concluding Steward could “Live to fight another day.”

That same year, MPT told investors and regulators that Steward was improving and on a path to being “strongly cash flow positive.” It again described Steward as its largest tenant by revenue — underscoring that its apparently lucrative properties were receiving supposedly consistent rentals.

By the start of 2023, analysts and the SEC began to question MPT’s business with Steward and the opacity surrounding their relationship. The SEC flagged that its special requests to MPT for it to submit Steward’s audits had not been met.

The SEC noted it was “unable to locate disclosure clarifying the nature of the assets that are associated with [Steward].”

In an October 2023 earnings call MPT continued to claim the hospital company was performing well, but in the following months MPT injected tens of millions into Steward via bridging loans.

In May 2024, MPT and Steward finally agreed to file for bankruptcy and put 30 of its 31 remaining hospitals up for sale.

In a press release announcing the bankruptcy, de la Torre said Steward had “done everything in its power to operate successfully in a highly challenging health care environment.”

Steward said it had over $9 billion in total liabilities, including $1.2 billion in secured debt, $6.6 billion in rent obligations, and nearly $1 billion in unpaid bills from medical vendors and suppliers.

But even in bankruptcy, the fight to control the hospital chain continues. Steward has filed an “adversary complaint” — a lawsuit filed within a bankruptcy case — accusing MPT of speaking directly to potential bidders for the hospitals without Steward’s consent, in a bid to get them to sign onto MPT’s leases.

The complaint claims MPT has pressured Steward to “accede to its demands that all value be siphoned to MPT, leaving the estates bare and risking the Debtors’ ability to maintain and sell their operations in a manner that maximizes value and safeguards patient health and safety.”

Brian Fitzpatrick (OCCRP) contributed reporting.